Gerhard Richter and Martha Rosler both adopted new ideas and cultures arising from the turbulent postwar era in Germany and the United States. Pop Art was especially influential to them in unshackling traditions of Socialist Realism and Abstract Expressionism. Richter and Rosler also incorporated photographs from mass media, which captured historical moments in World War II and the Vietnam War, into their works. Despite these similarities, what they sought from Pop Art and pursued in their artworks were completely opposite. While Richter was fascinated by the anti-artistic aspect of Pop Art, Rosler focused on how Pop Art brought a social landscape into art. As a result, Richter’s Pop-influenced paintings aim for the absence of statements while Rosler’s artworks convey strong political messages. These similarities and differences between Richter and Rosler can be found clearly by comparing two different pieces: Düsenjäger (1963) and House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-72).

Before delving into Richter’s and Rosler’s encounters with Pop Art, it is important to understand what political and cultural backgrounds they originally came from. To begin with, Richter was born and grown in East Germany where art was under the influence of Socialist Realism. The state controlled art to educate citizens, spread political doctrines, and idealize workers, farmers, and historical figures in the socialist society. Because art was meant to perform a social function, artists were forced to comply with the state ideology (Elger, 11-12). Under these circumstances, Richter worked as a mural painter and produced artworks conveying public messages. However, he became increasingly dissatisfied with his works; he believed that they were too mannered and inhibited. Richter thirsted for radical artistic departure from the norms of Socialist Realism, but it was impossible to be realized in East Germany (Elger, 29).

In 1959, Richter faced a crucial turning point when he seized on an opportunity to attend the exhibition Documenta 2 in Kassel, West Germany. He was utterly impressed by Number 32(1950), the abstract painting by Jackson Pollock, and realized that “there was something wrong with [his] whole way of thinking” (Buchloh, 1). To Richter, who had spent his life learning and practicing “compromised” art between capitalist and socialist ideologies (Buchloh, 1), Abstract Expressionism was “the emblem of artistic freedom” (Elger, 28). He recounted, “I realized, above all, that all those “slashes” and “blots” were not a formalistic gag but grim truth and liberation, that this was an expression of a totally different and new content” (Buchloh, 2). In 1961, Richter eventually left Dresden in East Germany and moved to Düsseldorf in West Germany to pursue his artistic freedom and “get away from the criminal ‘idealism’ of the socialists” (Elger, 15).

Meanwhile, Rosler came from an environment which was the exact opposite of Richter’s. Born and raised in the United States, one of the most capitalistic countries in the world, Rosler was trained as an Abstract Expressionist painter, a role that Richter in East Germany yearned for. However, as she continued with abstract painting, Rosler began to feel alienated from her works. First, there was a faltering of the dominant modernist paradigms of abstraction and transcendence in the United States. The reaction against Clement Greenberg as a single autocratic critic who established and promoted Abstract Expressionism became increasingly universal (Pachmanová, 98). Influenced by this flow, Rosler was critical of Greenberg and believed that he was the promoter of the high modernist painters whose her generation hoped to replace (de Zegher, 27).

More importantly, Rosler realized that Abstract Expressionism was not an adequate language to articulate her strong passion for politics. As a Jew, she grew up with a precarious sense that the Holocaust could happen again, and this fear was reinforced by the actual danger of nuclear conflict during the Cold War. She recalled, “It was a total paranoia. The rhetoric of war was applied by the United States to every single element of social life during the 1950s” (Pachmanová, 109). Therefore, it was natural for her to be involved with anti-nuclear protests, civil rights movements, and social justice issues. Abstract Expressionism, however, was too “abstract” and detached from her to express those political priorities. Rosler realized that “[she] actually do have something to say that can be translated into images as opposed to abstractions” (Murg, 2).

In short, Richter and Rosler were both unsatisfied with their artistic backgrounds. They noticed that traditional practices were too restricted for them to express their original ideas. Therefore, they sought alternatives, but in an opposite way. While Richter was tired of politicized art and admired Abstract Expressionism for its artistic freedom, Rosler perceived Abstract Expressionism as empty art and looked for politically inclined practices.

Then, Pop Art appeared to them as a potential solution. In Düsseldorf, Richter was absorbing Western artistic practices including Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Fluxus which were hardly accessible in East Germany. He also started to attempt new ways of producing art, such as integrating media images into his painting. Then, in 1963, Richter encountered a reproduction of Roy Lichtenstein’s painting Refrigerator (1962) in the January issue of Art International. The work was based on a newspaper advertisement showing a young housewife cleaning her refrigerator and beaming seductively at the viewer (Elger, 41). Richter was impressed by how “anti-painterly” it was (Buchloh, 7). Adopting the style of American comics, Refrigeratorwas an application of painting that left no trace of an artistic signature. Along with other Pop Art paintings, the works of Lichtenstein did not only suggest another example of producing media images in the painting. They also showed Richter that the artless subject matter and style of early Pop Art – a refrigerator, soup cans, comic books, and cheaply produced advertisements – could be an alternative way to escape from the narratives of Socialist Realism (Nasgaard, 48). He wrote, “Pop Art has rendered conventional painting – with all its sterility, its isolation, its artificiality, its taboos and its rules – entirely obsolete, and has rapidly achieved international currency and recognition by creating a new view of the world” (Elger, 16). As a result, Richter began to produce Pop-influenced artworks that negated artistic subject matters and practices. He especially focused on photographs from newspapers and family albums because they were produced through a mechanical lens of a camera, and therefore, they were “autonomous, unconditional, [and] devoid of style” (Elger, 30).

Similar to Richter, Rosler embraced Pop Art to get away from the Abstract Expressionist mentality. With the ascendancy of mass entertainment and consumer cultures, Pop Art was on the rise in the United States and made its break with high modernism. It allowed Rosler and her generation to challenge received narratives of art, culture, and power (Ho, 361). Pop Art also pointed her toward the direct use of images from mass media, such as old magazines and cheap advertisements. Following this direction of Pop Art, Rosler began to collect photographs from newspapers and magazines for her artworks (de Zegher, 25), just as Richter utilized media imagery for his paintings under the influence of Pop Art. However, Rosler was not interested in the anti-aesthetic aspect of Pop Art. Because she searched for a more concrete practice than Abstract Expressionism, Rosler accepted Pop Art as “a tantalizing model of art that refused to see itself as a mystical and transcendental projection, and, instead, promoted a possibility to engage art with the social in an incredibly potent way” (Pachmanová, 98). Mass culture imagery was not an artless subject matter or style to Rosler. Instead, it signified everyday lives, social interactions, and power dynamics. Therefore, by incorporating media images, especially photographs, into her artworks, Rosler attempted to bring a social landscape into art.

In brief, Pop Art provided Richter and Rosler with an alternative way to liberate themselves from received ideas, forms, and narratives. It also suggested the usage of mass media imagery in their artworks. Nonetheless, Richter and Rosler adopted different elements from Pop Art. While Richter was attracted by its negation of artistic practices, Rosler focused on its connection with society.

These similarities and differences between Richter and Rosler are expressed in various ways through their artworks, such as Düsenjäger and House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home.

Gerhard Richer. Düsenjäger. 1963. Oil on canvas. 130 cm x 200 cm. Catalogue Raisonné : 13-a

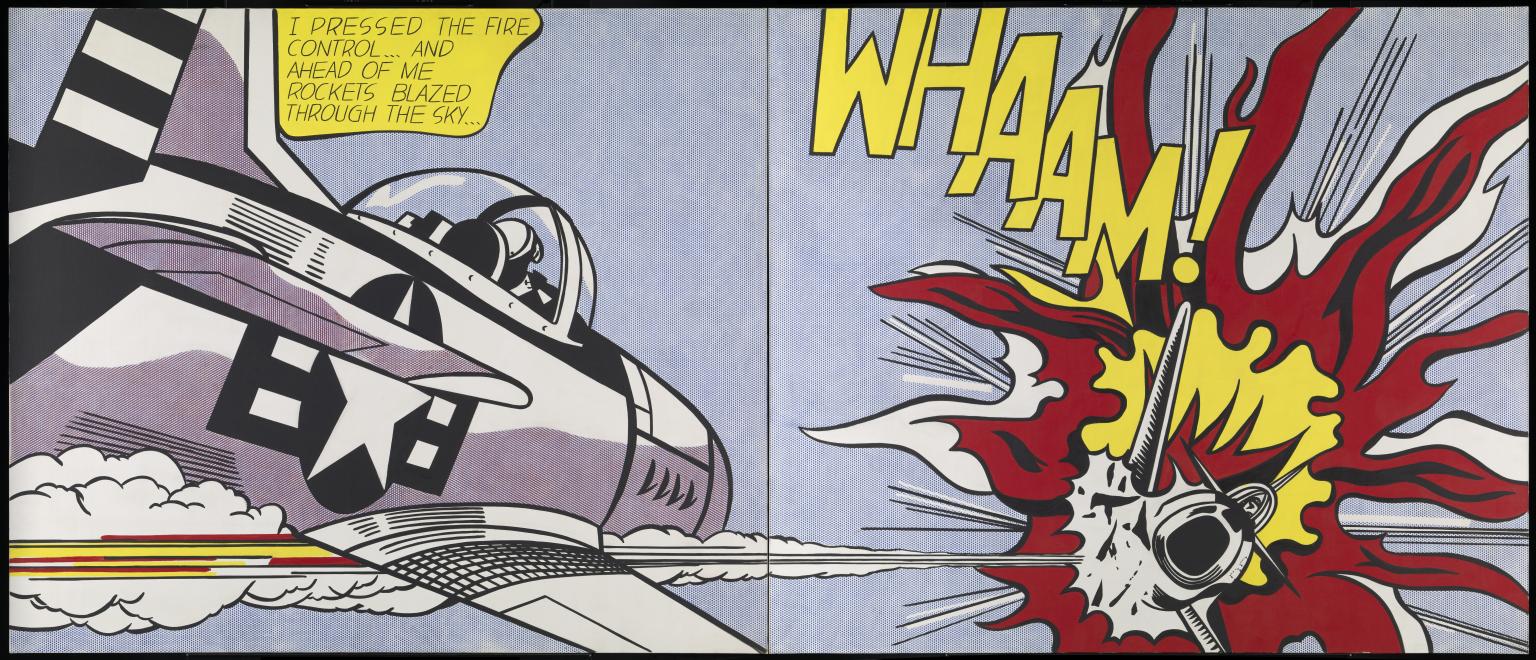

To begin with, Düsenjäger was painted by Richter in 1963. It is one of the warplane pictures created between 1963 and 1964. The object of this painting is a Fiat G-91, nicknamed “Gina,” which was an airplane that had been designed as a lightweight strike jet for NATO but ultimately employed by the Italian and West Germany air forces during World War II. Gina served as an image of the post-war rehabilitation of West Germany. It also featured in the press to promote NATO and West Germany’s role in the Cold War (Phillips, 1-7). Richter took a photograph of Gina from a newspaper and reproduced it in his oil painting. Interestingly, the subject matter of Düsenjäger is identical to Roy Lichtenstein’s Whaam! (1963) and its crude surface resembles the Death and Disaster (1945-1965) series by Andy Warhol. Needless to say, they are the most renowned Pop Artists in the world.

Roy Lichtenstein. Whaam! (Panel 1). 1963. Acrylic

paint and oil paint on canvas. 1727 mm x 4064 mm, Tate Modern Andy Warhol. Little Electric Chair. 1945-1965. Acrylic paint and silkscreen ink on canvas. 55.25 cm x 70.49 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

Therefore, it is not surprising that Richter declared that Düsenjäger is not an anti-war painting, although a warplane is a highly political subject. He said, “Pictures like that don’t do anything to combat war. They only show one tiny aspect of the subject of war – maybe only my own children feelings of fear and fascination with war and with weapons of that kind” (Storr, 59). At the time when he created Düsenjäger, Richter identified himself as a Pop Artist who refused to take anything seriously. With his colleagues Sigma Polke and Konrad Lueg, Richter stated, “We [artists influenced by Pop Art] were unable to see the statement in the work, neither the audience nor me. We rejected it. It didn’t exist” (Storr, 162). This attitude of negation was natural to Richter who strived to escape from Socialist Realism. He adopted Pop Art because he wanted to liberate himself from politicized art and pursue the freest and purest art form. Therefore, it was obvious for Richter to reject any concrete political meaning in Düsenjäger. He believed that art has an entirely different function from politics (Buchloh, 21).

Another element that heightens the sense of indifference in Düsenjäger is blurriness. Following the anti-aesthetic aspect of Pop Art, Richter did not blur his pictures to make a representation seem more artistic through lack of clarity or to give his style an individual tone. Instead, he aimed to neutralize what was depicted and retain the anonymity of an original photograph (Nasgaard, 49). Düsenjäger is no exception. It is impossible to identify the name or number of the aircraft due to its obscurity. Therefore, the object remains mysterious to viewers who do not have background knowledge of Gina. Also, the representation of its political stance during the war is in veil by the absence of information about nationalities, such as a flag or logo. At the same time, the out-of-focus quality provoked by blurring effects generates further distance in Düsenjäger. Its blurriness gives a sense of a frozen moment of speed, action, and activity. Therefore, it creates an illusion that the airplane would continue to fly away and the distance from it could never be narrowed.

To sum up, Richter’s Pop-influenced artwork Düsenjäger is a painterly reproduction of the warplane photograph from a newspaper. It is one of the earliest works of Richter’s photo painting directly influenced by the anti-art tendency of Pop Art. Therefore, Düsenjägerrefuses to convey any artistic or political statement and, with its blurring effects, it shows the neutrality, anonymity, and distance of the subject matter.

Rosler, who was also affected by Pop Art, produced artworks that incorporated photographs from newspapers, advertisements, and mass media. However, her photomontages present an opposite direction to the one that Richter’s photo painting suggests.

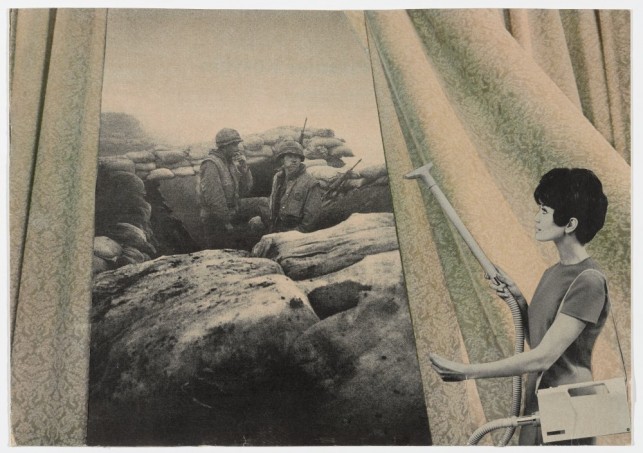

Martha Rosler. Cleaning the Drapes, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. 1967-72. Cut-and-pasted printed paper on board. The Museum of Modern Art.

In House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, Rosler put completely different images – photographs of the Vietnam War and commercial images from advertisements – together on a single canvas. For example, in Cleaning the Drapes, one of twenty pieces from Bringing the War Home, a stylish young housewife straight out of a vacuum cleaner advertisement effortlessly dusts the ornate drapes of her living room. However, as she lifts back the curtains, she witnesses the scene of soldiers in the trenches outside the window (Wetzler, 2). Rosler collected photographs of the war from Life magazines and images of advertisements from House Beautiful and other upscale interior design magazines (Ho, 352). Similar to Richter who incorporated photographs from newspapers into his paintings, Rosler applied images from mass media to her artworks.

However, while Richter rejected any political meaning in Düsenjäger, Rosler had a clear purpose in creating Bringing the War Home. She was struck by the bizarre coexistence of the Vietnam War and dinnertime in the United States. She noted, “By then the war was not only being discussed on radio and television news; the war, complete with battlefield film, was also broadcast on TV at dinner hour. Critics began to refer to the war as the first “living-room war,” though to me it was the dinnertime war. I wondered, “How do we eat dinner while watching a war! Had we no human feelings?”” (Ho, 349). Her disturbance resonates with what John Berger felt about the simultaneousness of two contrasting worlds in media. Just like Rosler, Berger was shocked by the fact that the photographs of refugees in Pakistan and the images from the Badedas bath commercial juxtaposed in a magazine were produced by the same culture (Berger, 152). Alarmed by this ironic situation, Rosler produced photomontages that directly brought the war images into pictured homes. This new “space” of colliding imageries was where she wanted to invite the viewer in, to stand and think (Ho, 352). She explained, “I wanted people to be able, in their imagination, to step into that room, and to think about it as their room. And to see what was happening there in the room, or right outside the window” (Hubber, 3). By doing so, Rosler allowed the audience to observe war scenes in and around an idealized American home; she wanted to remind people of the unity, not the separation, of the worlds in which the war was taking place and in which people in the United States live (Ho, 352). This invitation to engage with the artwork presents a striking contrast with the permanent distance in Richter’s photo painting. While the airplane in Düsenjäger seems almost unreachable to viewers, Cleaning the Drapes allows audiences to locate themselves in the same spot as the housewife and watch the tragic scene of war outside the window.

Also, unlike Richter who blurred his pictures to diffuse the individuality of an object (Elger, 88), Rosler highlighted the identification of each subject matter. To her, Americans during the Vietnam War seemed to oscillate between identification and non-identification with the Vietnamese being killed “over there,” consoling themselves that those victims and refugees were not, after all, like them “over here.” (Ho, 351). Rosler wanted to break this compartmentalization. Therefore, by producing Bringing the War Home, where the distinctive images of two different worlds collide, she brought people (Vietnameses and soldiers) who associated with another world, the “there,” into “here” so that the audience (Americans) could recognize and identify with them (Lewinson, 3). For example, in Cleaning the Drapes, Rosler did not erase or obscure the individualities of the soldiers in the trenches and the housewife in her cozy living room. Instead, by highlighting and juxtaposing these disparate images, she delivered a message that people are not a here and a there but all one (Hubber, 2).

In conclusion, Rosler clearly addressed anti-war statements in Bringing the War Home by allowing audiences to place themselves in the new space of colliding images and identifying themselves with people who resided “there.” Because she adopted Pop Art to get away from the emptiness of Abstract Expressionism and bring a social landscape to art, it was natural for Rosler to create artworks that convey strong political messages. She stated, “Acting together with full-throated social protest, such works can encourage a rethinking and rejection of the arguments usually made in favor of distant wars that we may view only on our screens. Condensing an argument by offering a different framing of the issues is one of the things that art can help us do” (Ho, 354). Her statement forms a striking contrast with the one made by Richter – “Pictures like that don’t do anything to combat war. They only show one tiny aspect of the subject of war” (Storr, 59). They both embraced Pop Art as a new artistic language to liberate themselves from traditional practices. They also actively incorporated images from mass media into their artworks. However, they accepted different elements of Pop Art. Therefore, the results turned out in a completely different way; while Richter created the anti-aesthetic painting with the absence of statements, Rosler produced the anti-war photomontages delivering strong political messages.

Interestingly, The War Series (1966-1970) by Nancy Spero encompass both similarities and differences between Richter’s and Rosler’s works. What motivated her to produce the series were the images of the Vietnam War in mass media. Therefore, just like Richter and Rosler, Spero utilized war photographs from newspapers and broadcasts in her artworks.

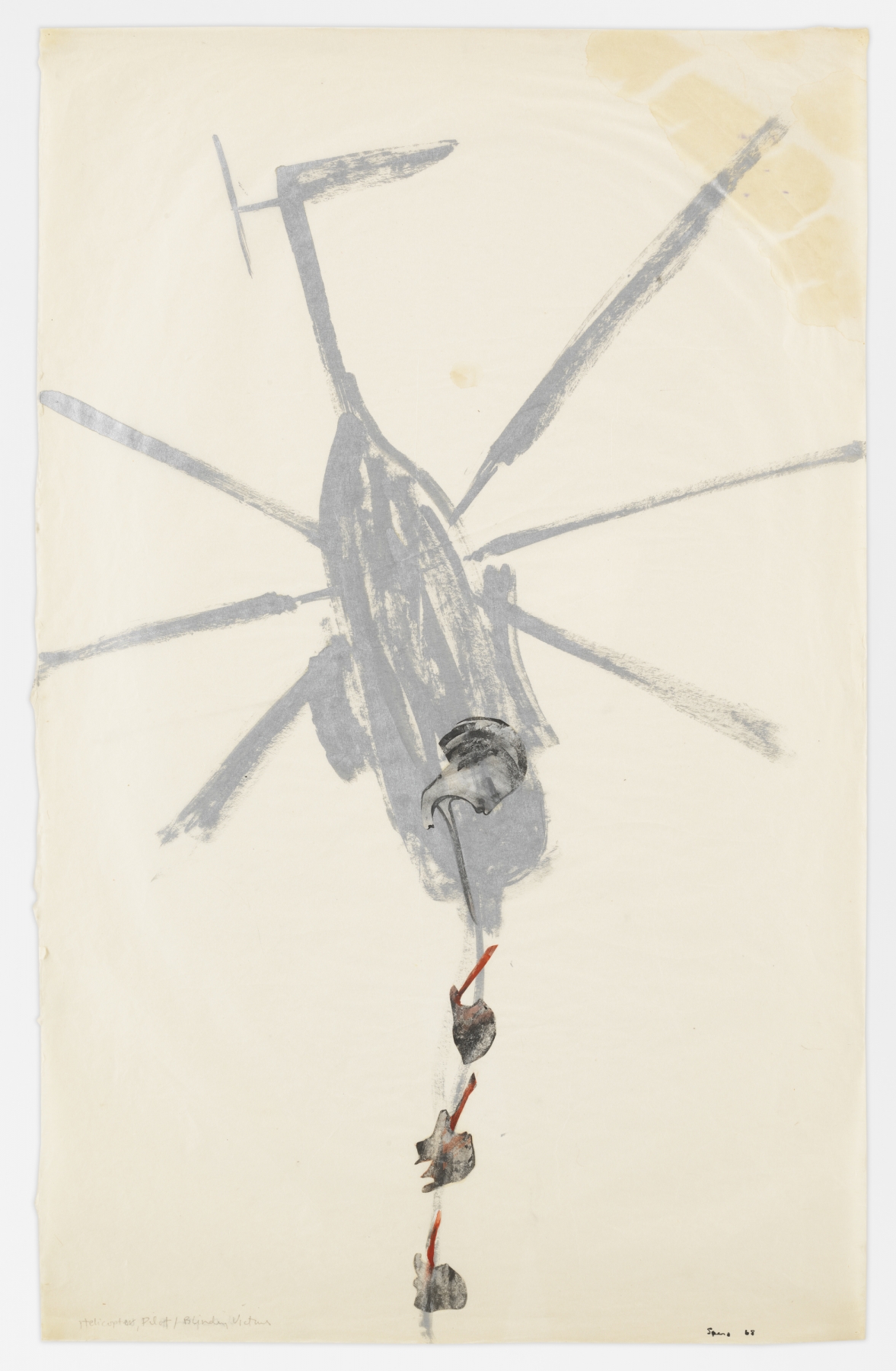

Nancy Spero. Blinding Victims. 1968. Gouache and ink on paper. 91.4 cm x 61 cm. Galerie Lelong & Co.

Blinding Victims (1968), one of the paintings in The War Series, illustrates the horrific scene of a giant insect-like helicopter holding a rope of decapitated heads. Similar to Richter who reproduced the photograph of a warplane in his painting, Spero collected images of helicopters from newspapers and used them as a reference for her picture (Enright, 4). She also deliberately worked on paper because she believed that it was “a radical and self-propelled process” (Enright, 6). Therefore, just like the Gina in Düsenjäger, the helicopter in Blinding Victims is depicted in a flat form, but its rough and blurry silhouette implies the violent movement of the machine. Meanwhile, Blinding Victimsresembles Bringing the War Home because it is clearly anti-war. Spero was appalled by uncensored images of the Vietnam War broadcasted on television all the time and felt a responsibility to address these issues in her works. Her statement – “I see things a certain way, and as an artist I’m privileged in that arena, to protest or say publicly what I’m thinking about” (ART21, 3) – resonates with Rosler’s aim to express her political priorities through art. Nevertheless, Blinding Victims has its own uniqueness, too. Compared with Richter’s mechanical illustration and Rosler’s humorous approach, Spero’s drawing is much more emotional and expressive, just as she described The War Series as an act of “personal exorcism” (Enright, 6).

In conclusion, the works of Richter, Rosler, and Spero all suggest different approaches and insights to art, mass media, communication, war, violence, politics, and “here and there.” We cannot deny that their ideas and practices are even more relevant to our current society where media is overly saturated and wars are still ongoing.

Notes

1. Barragán, Paco. Interview with Martha Rosler. ARTPULSE Magazine. http://artpulsemagazine.com/interview-with-martha-rosler

2. Berger, John. (1972). Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books

3. Buchloh, H. D. (Eds.). (2009). An Interview with Gerhard Richter. In Gerhard Richter. The MIT Press. http://mitp-content-server.mit.edu:18180/books/content/sectbyfn?collid=books_pres_0&id=7697&fn=9780262513128_sch_0001.pdf

4. Elger, Dietmar. (2009). Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting. University of Chicago Press.

5. Elger, Dietmar. (Eds.). (2009). Gerhard Richter: Writing 1961-2007. D. A. P.

6. Elger, Dietmar. (Eds.). (2011). Gerhard Richter: Catalogue Raisonné. Volume 1 : Nos. 1–198, 1962-1968. Hatje Cantz.

7. Enright, R. (2004). Picturing the autobiographical war: Nancy Spero's War Series. Border Crossings, 23, 50-61.

8. Enright, R. (2000, 11). On the other side of the mirror: A conversation with Nancy Spero.Border Crossings, 19, 18

9. Ho, Melissa (Eds.). (2019). Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975. Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press.

10. Hubber, Laura. (2017). The Living Room War: A Conversation with Artist Martha Rosler. The Iris (a blog of the J. Paul Getty Trust) https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/the-living-room-war-a-conversation-with-artist-martha-rosler/

11. Lewinson, Ann. (2018). Art in Resistance: A Conversation with Martha Rosler. The Rumpus. https://therumpus.net/2018/12/31/the-rumpus-interview-with-martha-rosler/

12. Murg, Stephanie. Interview with MARTHA ROSLER, The Artist Who Speaks Softly but Carries a Big Shtick. PIN-UP Magazine.https://pinupmagazine.org/articles/interview-with-brooklyn-artist-martha-rosler-jewish-museum-nyc-survey-show

13. Nasgaard, Roald (1988). Gerhard Richter. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

14. Pachmanová, Martina (Eds.). (2006). Martha Rosler: Subverting the Myths of Everyday Life. In Mobile Fidelities: Conversations on Feminism, History and Visuality. KT press. https://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue19_Martina-Pachmanova_98-109.pdf?

15. Rosler, Martha. (2004). Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975-2001. The MIT Press in association with International Center of Photography.

16. Storr, Robert. (2002). Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting. Museum of Modern Art.

17. Storr. Robert. (2009). Gerhard Richter: The Day Is Long. ARTnews. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/gerhard-richter-robert-storr-62780/

18. Storr, Robert. (2010). September: A History Painting by Gerhard Richter. Tate Modern.

19. Wetzler, Rachel. (2019). The Art of Irreverence: Martha Rosler’s War on Complacency. Jewish Currents. https://jewishcurrents.org/the-art-of-irreverence-martha-roslers-war-on-complacency

20. de Zegher, Catherine. (1998). Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World. The MIT Press.

21. Capitalist Realism and Richter. Phillips. https://www.phillips.com/article/7010732/richter-dusenjager

22. Politics & Protest. (2011). Art21. https://art21.org/read/nancy-spero-politics-and-protest/